Why did you become an architect?

Construction and architecture had always been in my family, so I always had both in my life. My paternal grandfather was an architect. He trained and worked in Germany, immigrated and ended up in Oregon. My maternal grandfather was a builder in Oregon.

I wasn’t sure what I wanted to be when I went to the university. Like many students, I tried different subjects such as drawing, sculpture and photography classes, and I spent time in the art and architecture building. It was inspiring, and I felt the pull in the arts. Of all the arts, architecture felt like the right choice because of my experience growing up.

You studied architecture at the University of Oregon and graduated in 1995. What was the most important thing you learned as part of your university education?

I didn’t know much about architecture when I started, even though I had experience. What had the biggest influence was how the School of Architecture program opened my eyes to what architecture is and can be. During my time there, I began to understand and appreciate architecture. It opened my eyes to a way of thinking about architecture that was really just the beginning.

How has your work as an adjunct instructor at the University of Oregon, School of Architecture, helped you as an architect?

Teaching requires me to explain things clearly and precisely. I have summarized and organized my approach for achieving clarity, and I teach it to students throughout the course as a framework. It is not formulaic, but it helps students think about how to design their own projects.

What has been the most significant work experience you’ve had so far during your career?

After my experience at the University of Oregon, I left the U.S., moved to Europe, and worked for three years in Renzo Piano’s RPBW Architects studio. He is one of the most famous living architects, and he has projects all over the world.

Professionally, my experience at RPBW Architects was extremely formative because it combined seeing, experiencing and working. I worked with a group of extremely talented architects. In addition to being around them, I was also around some of the most important projects in the office at that time, and I gained an understanding of how the workshop operates. RPBW Architects is in Genoa, in northern Italy. Since it is near the Mediterranean and close to Switzerland, I spent a lot of time in Switzerland, too, and I met many Swiss architects.

How have the awards you’ve won as an architect affected your professional development?

When you submit for an award, you are telling a story. I want to be precise about telling that story to others, and the submittal preparation process helps me be very clear about a project’s importance. After telling the story, I better understand what did and didn’t work, and I learn from that. It helps me move on to the next project.

An AIA Idaho biography about you said you started Waechter Architecture “to pursue experiential and clear, distilled design concepts for a wide range of building types and scales.” Would you please tell us more about that?

The buildings that resonate with me and the architects at Waechter Architecture have a strong sense of character and vividness. Even though many design aspects are important, the word “clarity” captures the experiential precision we want. Thinking about clarity grounds our approach as we work on individual projects.

The clarity project has become an overarching project. We take a step back and ask ourselves, why are we designing buildings and what is important about their design? We’ve developed different techniques to apply to our work, but all of them are under the umbrella of clarity.

- Spatial composition or order is an important starting point for us. We want to understand how it feels to be in a building space. Spaces are affected by the shape and proportion of the rooms. For example, how tall is the room relative to its width and length? As we adjust those proportions, how do the adjustments make the space feel different? When we shape the size and proportion of spaces, we also consider complementary spaces. How can an entry sequence or moving through different spaces affect how people feel about occupying a building or a space within the building?

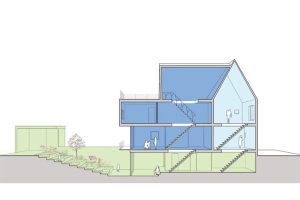

- We also work toward clarity of composition. The places that feel the best to be in have simple and distilled floor plans and elevations, but there is a balance between simplicity and functionality. We work hard to try and make our floor plans, elevations, and sections as simple as possible while still being functional.

- We like to have clarity within the material palette. We limit the number of building materials because that allows them to have a stronger sense of identity and character.

What has your experience been like as a juror for AIA Idaho annual award competition? How have the project evaluations you did for the competition influenced you professionally?

It is always really interesting and fun to visit a new community of architects. We share many things even though we come from different locations, political views and economic situations. I benefit from understanding other people’s challenges and responsibilities and learning about their opportunities, constraints and responses to their unique situations.

Which project for the 2021 competition did you enjoy the most? Why?

All the projects were really interesting. I don’t have a specific project in mind, but there were a lot of single-family house entries this year. The strongest projects tended to be where the architects could solve all a house’s requirements as simply as possible.

I also enjoyed seeing how the houses were placed. Some of the houses seemed like just a speck when I compared them to the big, natural beauty of the Idaho landscapes, but their simplicity allowed them to coexist gracefully with their surroundings.

In 2021, the World Population Review listed Idaho as the fastest-growing state in the U.S. Do you have any suggestions for Idaho’s architects as they meet the newcomers’ needs?

Every community in the world is facing this problem, not just Idaho. Globalization opens up all sorts of opportunities, which is great, but from an architect’s view of the built environment, there’s also a risk of sameness that can happen.

As architects, we all need to carefully understand what is unique about a particular environment, its culture and the history of the existing buildings in the area. Then we need to design buildings that support the environment’s uniqueness, whether that means the form, the materials or both, so we can continue the dialog of what is unique about a particular place.

Supporting an environment’s uniqueness doesn’t mean imitating old things. It is possible to design buildings that respect the older buildings while still clearly being new.