Why did you become an architect?

I was interested in design from a young age because of a house my great-grandfather built in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. My interest in architecture is an outgrowth of that.

The house is on the southwest corner of Cape Cod. He used timber harvested from Oregon in 1928. I grew up in the suburbs of Washington D.C., but I would come to his house in the summer. It was a very small, simple house. I always admired its materiality and the craft that had gone into putting it together. The wood wasn’t finished, and you could see the fingerprints of the people who had put it together. I liked how it felt to be there.

You studied architecture at the University of California, Berkeley and Harvard University Graduate School of Design. What was the most important thing you learned at either or both schools?

The two schools had different approaches, and I got a lot out of my time at both. I was fortunate to be at Berkeley, which had incredible and brilliant professors. My education there was focused on the arts and design. During my first semester, all we did was hand drawings. It was just a pencil on paper, and you never had a straight edge. We studied art, aesthetics, composition, drawing and sculpture. There was also a great building sciences department where the professors focused on subjects such as daylighting, sustainability and indoor air quality.

After Berkeley, I worked for several years, and I was licensed before I went back to the design school at Harvard. That experience opened my eyes to a broader, more international world of architecture. People all over the world gave lectures.

One of the most amazing experiences I had there was with Peter Zumthor, who wasn’t as famous then as now. That was a highlight of my graduate school experience. Meeting him led me to move to Basel, Switzerland, with my wife. I worked at Herzog & de Meuron for three years.

How did the two educational experiences differ?

They were different but complementary. Berkeley focused on building sciences. You learned how to make things from different materials. Harvard was much more connected to what is happening internationally. We also looked at larger issues around theory and how intellectual movements impact the production of architecture.

How has your work as the USDA Wood Innovation Grant Visiting Professor at the University of Arkansas helped you as an architect?

The Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design at the university focuses on innovation specific to timber. It was great to share what I had learned about mass timber buildings.

What has been the most significant work experience you’ve had so far during your career?

We were part of the team that won the 2015 U.S. Tall Wood Building Prize Competition. We used a $1.5 million grant to develop a high-rise wood building design and pay for the testing and modeling to demonstrate that tall wood buildings are possible. We worked with national and international engineers and research scientists. The project has impacted international building codes and how people think about tall wood buildings.

How have the awards you’ve won as an architect affected your professional development?

Rewards are gratifying, but the real reward is the work itself and knowing clients love the spaces that you’ve created.

Why did you start LEVER Architecture?

In 2009, when I started LEVER Architecture in my basement, I had already begun thinking of architecture as more than an end in itself. I was fortunate to have great relationships with people I worked with through the years. Opportunities came up when I started telling people I was on my own, and after a while, I found some office space. Now we have 42 people.

We have been open to insights from our long-term collaborations with consultants, contractors and subcontractors. Our most successful architecture reflects a strong work relationship with everyone involved.

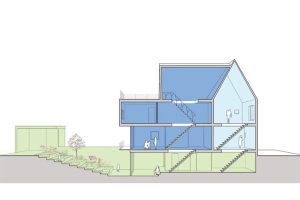

What something is made of always interests us, and we design buildings around material characteristics. We leverage material to do even better what it can already do really well. In the case of wood or timber, we know what it can do better than other materials and what it does not do quite as easily. That understanding is our framework as we think about the design.

What has your experience been like as a juror for AIA Idaho annual award competition? How have the project evaluations you did for the competition influenced you professionally?

I was excited to be a juror. I grew up hiking in the mountains, and I had always heard amazing things about Ketchum and Sun Valley, but I’d never been to Idaho or spent any time there before. Idaho’s incredible landscape was interesting. I spent some time in Sun Valley, and I enjoyed meeting the architectural community.

It’s good to get out of the environment you are used to and see what other people are doing in a different landscape and place.

Which project for the 2021 competition did you enjoy the most? Why?

For me, it was a wonderful surprise to find innovation in places you are not as familiar with and don’t expect. Buildings for an insulation company or a high-end heating and cooling company can become amazing pieces of architecture. Architecture can come from anything, and it can come from any program. It can be part of your everyday life.

We gave VY Architecture a commercial architecture honor award for a project called EnergySeal. The building is for a company that installs insulation, and it demonstrates how you can bring a richer experience to people’s everyday lives. Because being in an extraordinary everyday building is as valuable as spending time in a French cathedral.

In 2021, the World Population Review listed Idaho as the fastest-growing state in the U.S. Do you have any suggestions for Idaho’s architects as they meet the newcomers’ needs?

We should collaborate now and advocate for good decisions.

Idaho’s primary strength is the landscape. If you spoil something, you can’t easily unspoil it. But if you aren’t thinking long-term about the impact of how you grow, it’s very easy to lose what’s special about a place like Idaho and the west in general.

Growing without a plan is always a danger because it takes place without thinking about the impact of growth on the larger ecosystem in 10 or 20 years. But that impact will lead to an environment from which people will want to escape.

Architects are always working on making the future real. They use their skills to demonstrate or visualize what different types of growth will mean, how they can impact that future, and maintain the strengths that make people want to come to Idaho in the first place.

Any last words?

Design is connected to the materials you find or potentially harvest from a particular landscape. Hopefully, that connection is something people can recognize that makes them feel more connected to a place.

LEVER Architecture has a set of goals and principles that we use to create the experiences for people in our buildings. We’re very interested in setting off with a shared set of experiences and principles and the client’s or community’s aspirations. It is a team effort. My goal is always to ask whether we are keeping our eyes on those initial principles. Are we creating spaces that move people and allow them to do their best?

The way a tool is used to do something is what is meaningful. It isn’t about the tool itself. If you put a lever in the right place and know how to use it, you can move the world.