We always want our buildings to have a conversation with the landscape,” said Faith. “For this project, we created the five little huts from kits that can be put together to create art studios. People can camp wherever they want on the land, which is hilly and bold, and each placement creates a different conversation. The buildings are very gestural, and they are almost like characters.”

Faith Rose of O’Neill Rose Architects spoke about the concept of home at the 2021 Idaho Design Awards ceremony on Sept. 24, 2021. She pointed out that for the last 20 months, COVID-19 has shaken up many people’s ideas of home. But even before that, changes in communities and societies were increasingly reflected in peoples’ homes.

As part of Faith’s presentation, she highlighted three examples of change that O’Neill Rose Architects has explored:

- Multigenerational houses

- Aging-in-place houses

- Live-and-work environments

The Projects A Multigeneration House

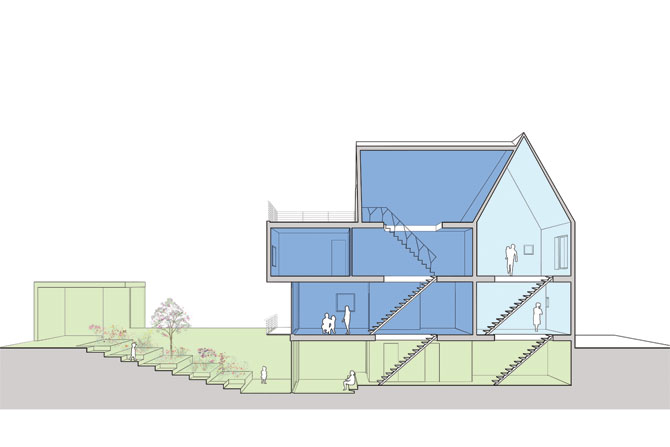

Queens, New York, one of New York’s five boroughs, is one of the world’s most ethnically diverse urban areas. It is a patchwork of unique neighborhoods, each with its own identity. However, the borough’s housing stock consists primarily of single-family homes built in the 1950s, when architects designed homes for the American nuclear family.

A client at O’Neill Rose Architects asked for a multigenerational home to accommodate three generations and three distinct groups in one home.

- The client, his wife and their two small children

- His younger brother and his sister-in-law

- The mother of the client and his younger brother

Each group needed to have its own space. Also, the home had to comply with code and zoning requirements that, among other things, had been written to force the construction of pitched roofs.

Faith said, “We asked ourselves, ‘How do we create a home that honors the communal living conditions of their old country, but also recognizes the younger generation will want the more American values of privacy and space?’

“We decided to create three disparate dwellings with areas that connected and overlapped. Each dwelling had clear boundaries, but the home’s circulation wove through all of them, connecting them to each other.” As Faith explained:

The family matriarch was on the ground floor. Above the ground floor were apartments for the brothers’ families. These two-level apartments share the second and third floors.

The family matriarch insisted that her sons’ homes be connected to her apartment by stairs. O’Neill Rose Architects suggested excavating the land behind the home to bring light into her apartment, and she decreed that the backyard would become a terraced garden. She uses the space to grow food and medicinal herbs. The entire family could hang out in the ground-floor family room, next to the garden, and the stairs made it easy for the grandmother to watch her grandchildren on the second and third floors.

The multigenerational home had a modest budget. To keep costs down, the architects repurposed materials when possible. For example, leftovers from engineered wood beams were sliced in half diagonally to make treads. The treads were inserted onto pins attached to steel stringers. A semi-opaque white screen separated the stair from a seating area; it was built from polycarbonate panels held in place with a single peg.

Aging in Place

The next project Faith presented was built for the housing-related needs of older adults. The average age of the U.S. population is increasing because more and more of its citizens are retirement age or older, even after the pandemic. As a result, O’Neill Rose Architects has been looking at the needs of older adults. Faith said, “Studies have shown that there are many benefits to aging in place, particularly when it comes to mental health. In turn, [many design elements] lend themselves to creating spaces that support positive aging in place.” She also noted that physical activity in green spaces improves mood and cognitive function and decreases depression and stress.

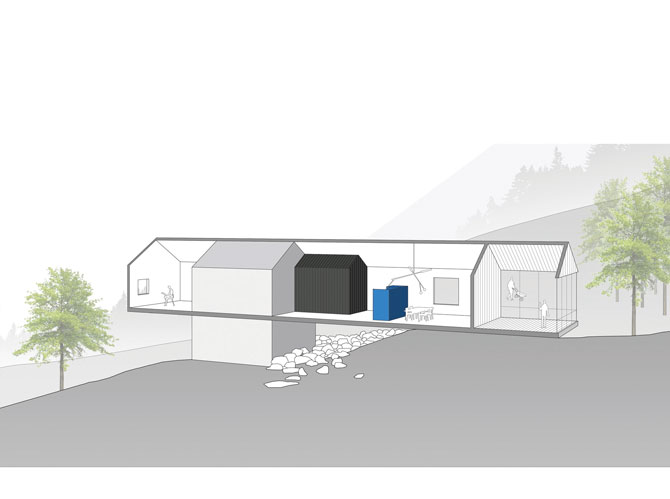

The Undermountain House project was designed for growing old gracefully. The clients loved nature, and they wanted to continue experiencing it as they aged and became less active. The home is set like a stitch in the land. It was built on a single level and sited to “experience the full motion and beauty of the land” from different heights, said Faith. Although the home is immobile, the landscape rolls around and underneath the home to create a sense of motion. The sun moves through the space throughout the day. Residents can see the orchard, the pond and the woods through large windows. Small windows frame views of the rain garden, the woodpile and meadow flowers. (The architects included a low, tiny window for the family dog to see the rain garden. The rain garden has boulders and an outdoor staircase on one side.) Windows at one end of the home focus on the tree trunks. Windows on the other end show swaying treetops and sky. There is also a screened-in porch.

In addition to the dog’s rain-garden window, the lower level has en suite bedrooms for the client’s children. The lower level will be the caretaker suite later on.

The surrounding area has many agricultural buildings to which the home responds. It has a simple barn-like shape. The stone base anchors the building, and lighter wood framing floats above. The house extrudes across the hilly ground plane so that the main floor is at ground level on one end and floats 10 feet above grade at the other end. The stone garden follows the natural grade and slips under the center part of the house. The rain garden allows rainwater to sluice through the boulders and run down to a wetland pond.

A Live-and-Work Environment

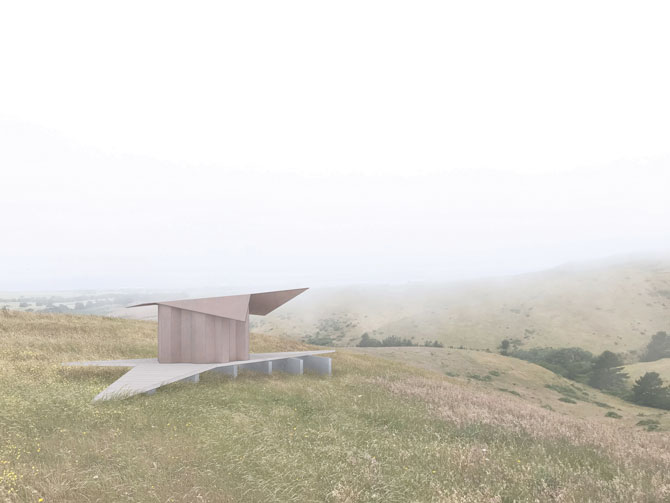

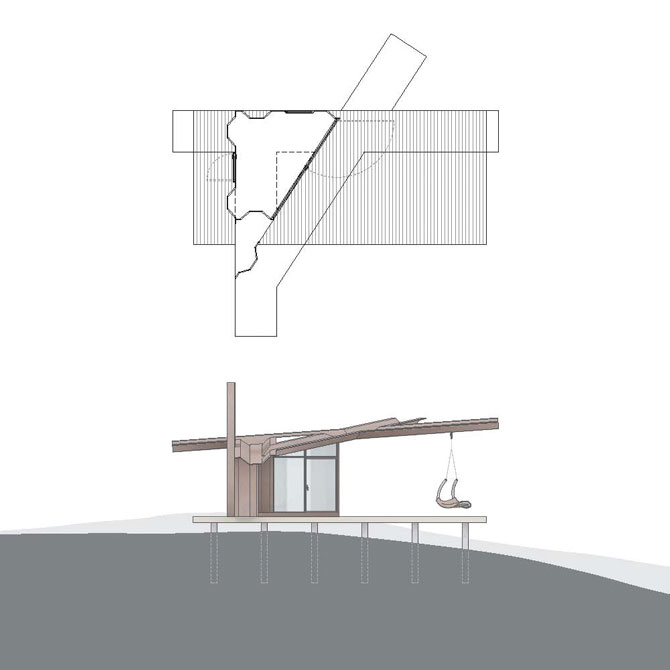

The third project Faith described was the complete opposite of the second one. It is located on 400 acres of coastal agricultural land in Bodega Bay, California, and the Pacific Ocean is visible in the distance. A sculptor owns the land, but a rancher uses it.

The sculptor asked O’Neill Rose Architects to create studios to house visiting artists for his art colony, with an existing barn with a gallery and communal kitchen serving as the colony’s center.

Each one-person studio had to abide by the migrant workers’ housing rules, which meant they could only be occupied for 90 days at a time. After that, they have to be disassembled. The primary building materials were taken from the sculptor’s nearby sculpture yard. They included steel sheet piling, heavy timber and bolted connections. The sculptor moves the huts to a new location every 90 days with a forklift and a small crane that also move sculptures.

“We always want our buildings to have a conversation with the landscape,” said Faith. “For this project, we created the five little huts from kits that can be put together to create art studios. People can camp wherever they want on the land, which is hilly and bold, and each placement creates a different conversation. The buildings are very gestural, and they are almost like characters. Their relationship to the land depends on where they are located. A llama guards some of the cows, so one studio has a flat roof with eaves that touch the ground like ramps. That way, the llama can climb up and survey the land.”

The small studios have a minimal footprint on the land, and their size encourages artists to spend most of their time outside.

Idaho’s Challenge

Architects have an ongoing opportunity to redefine the types of homes they work on. The pandemic, climate change and rapid population growth are all changing the parameters of what a home is. The idea of homes and how they should function was called into high focus during the pandemic, with people confined in tight spaces that had to function for multiple uses. Many people experienced isolation and familial frustration, but they are now finding new opportunities for remote work that are changing the rules for how and where they can live.

As Idaho’s population continues to grow, applying smart-growth principles is the best way to preserve Idaho’s beauty and quality of life. Implementing ideas such as making cities denser to create walkable neighborhoods and distinct, attractive communities can prevent urban sprawl; likewise, buildings that use sustainable materials and practices can minimize the built environment’s impact.